Black History in the Cold Chain: George Washington Carver

February 09, 2023

All month long, Lineage is recognizing the mighty contributions made by black pioneers and innovators in supply chain logistics. Earlier, we learned about Frederick McKinley Jones’ invention of the first automatic refrigeration system for long haul trucks and how it enabled refrigerated transportation as we know it today. This week we’re meeting George Washington Carver, whose inventions and discoveries changed agriculture forever.

The Birth of “The Plant Doctor”

George Washington Carver was born into slavery sometime in 1864, in southern Missouri. He never knew much about his family growing up, having lost his father to an accident shortly before being born and his mother to slave raiders shortly after he was born. Health problems prevented him from working in the fields; instead, he focused on learning.

George had a deep love of plants from an early age. He spent much of his childhood wandering the woods and fields near his home, observing plants, animals and fungi. George began experimenting with different plants and soil conditioners as well as natural pesticides and fungicides. He became skilled at diagnosing plant ailments, earning himself the nickname “The Plant Doctor” from nearby farmers. It was his passion for botany, chemistry and agriculture that led George to transform agricultural practices in the South forever.

The Education of George Washington Carver:

- Started his college education at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa.

- Continued his education at Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University), where he earned his Bachelor of Science in 1894. He was the first African American to do so.

- In 1896, he topped it off with a Masters of Science in agriculture and bacterial botany.

- Carver was invited to the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama, to teach and build the school’s Agriculture Department. This was where the magic happened.

The Tuskegee Institute and Carver’s Agricultural Revolution

Carver established the Agricultural Research Station at the Tuskegee Institute and became its first director in 1896. He spent the next 57 years using his vast knowledge of plants and chemistry to develop innovative solutions to many of the challenges facing farmers and communities in the Southern United States. His impact was nothing short of a revolution and continues to be seen on farms and in grocery stores today.

Many of the problems southern farmers faced revolved around soil fertility, pests and nutrition. Cotton was the main cash crop in the South at that time, but these plants were leaching the soil of its vital nutrients, affecting crop yields and quality. Farmers had to continue growing more of it, eventually replacing many of their food crops and having an effect on regional nutrition. This, combined with the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914, led to food shortages and rationing across the US.

Cotton was facing another problem at the time, boll weevils. These nasty pests were decimating cotton fields between 1914 and 1917. Their nearly total reliance on cotton meant the boll weevil infestation was devastating the lives of southern farmers. Entire counties were losing upwards of 60% of their cotton crops.

Carver came up with several solutions. He taught farmers new methods of sustainable farming, including crop rotations and the use of natural compost. Rotating in new crops helped farmers diversify their yields, protecting them from being too reliant on just one crop. He even found the perfect crops for them to plant: soybeans, sweet potatoes and peanuts. These plants all acted as soil conditioners, replenishing and redistributing important nutrients back into the soil.

Farmers were skeptical at first because, at that time, there weren’t many commercial uses for these crops. Carver solved this problem by developing and publishing hundreds of new and existing uses for peanuts, soybeans and sweet potatoes, giving farmers hundreds of reasons to plant these crops. The wide variety of uses, from food to fuel, encouraged farmers to take the chance and make the change.

George Washington Carver’s Lasting Legacy

Carver’s work in agriculture led to a revolution in how farmers grew their crops. Farmers were able to grow more food, revitalize their soil and prevent erosion by planting crops like soybeans, sweet potatoes and peanuts. This influx of new food products helped create new markets for these crops, reducing the South’s dependence on cotton and greatly improving the livelihood of farmers across the region.

To this day, farmers utilize his methods of sustainable farming to increase their yields and feed more people. Many of the products Carver helped develop can still be found in grocery stores and on Lineage trucks all around the world.

Sources for this Article:

- Alabama Historical Commission Editors. (n.d.). History of Agriculture in Alabama: A Historical Context. Retrieved from https://ahc.alabama.gov/architecturalprogramsPDFs/History%20of%20Agriculture%20in%20Alabama.pdf

- George Washington Carver Museum, National Park Service Editors. (n.d.). Learn About George Washington Carver. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/gwca/learn/historyculture/index.htm

- History.com Editors (2022, August 29). George Washington Carver. History.com. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/george-washington-carver

- Invent.org Editors. (n.d.). How George Washington Carver Revolutionized Agriculture. National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved from https://www.invent.org/blog/inventors/george-washington-carver-inventions

- Jernigan, M. (2022, August 1). Defeating the Boll Weevil. Auburn University College of Agriculture. Retrieved from https://agriculture.auburn.edu/150-years-celebration-ag-engineering/defeating-the-boll-weevil/

- Johnson, C. (1900). George Washington Carver and Student. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved from https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.92.156

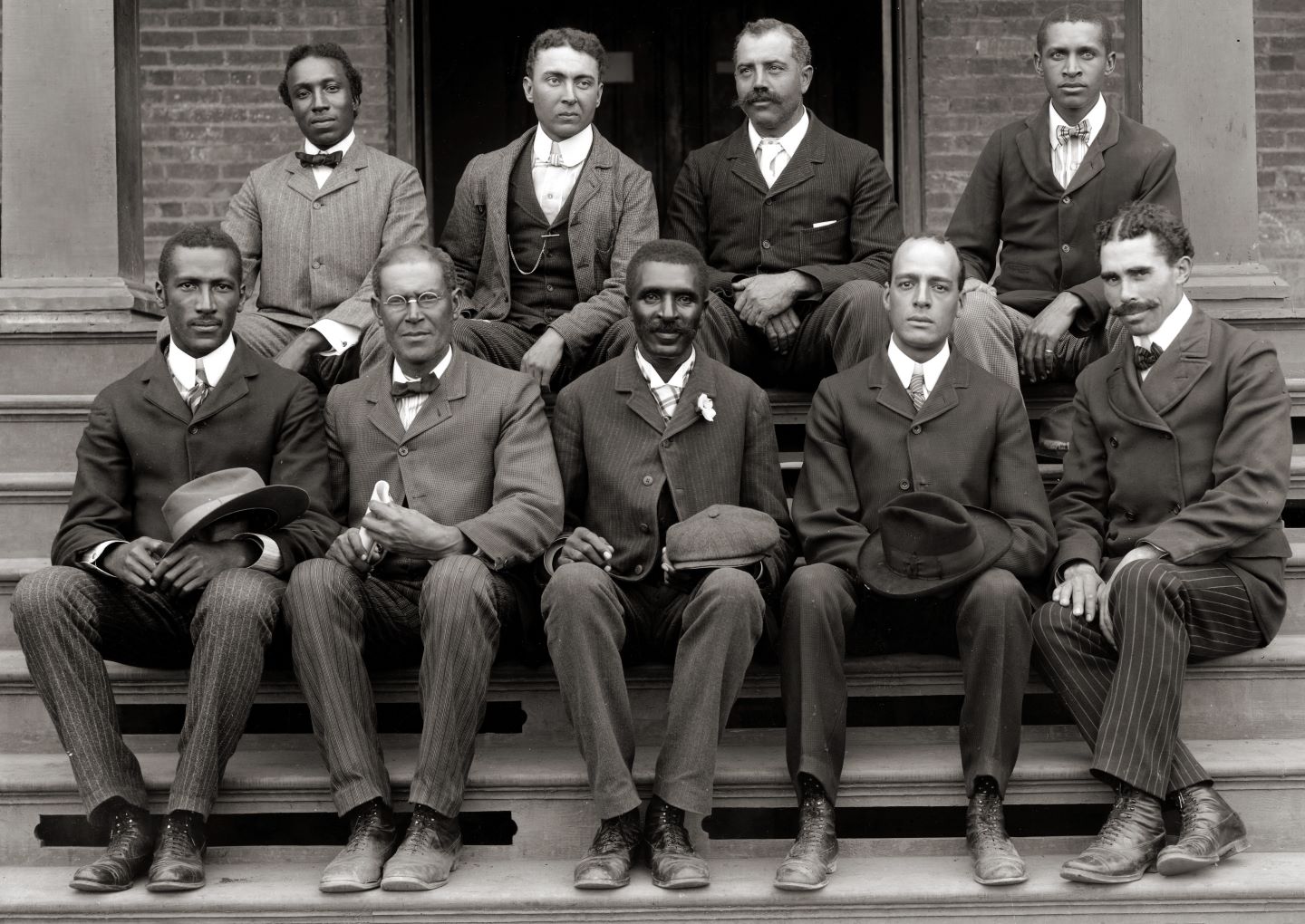

- Johnston, F.B. (1902). George Washington Carver, full-length portrait, seated on steps, facing front, with staff. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004671560/

- Kosmerick, T. (2017, August 18). World War I and Agriculture. North Carolina State University Libraries. Retrieved from https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/news/special-collections/world-war-i-and-agriculture

- Missouri Department of Agriculture Editors. (n.d.). George Washington Carver: History of an Educator, Innovator, Leader. Missouri Department of Agriculture Retrieved from https://agriculture.mo.gov/gwc.php

- Wright, J. (2021, February 2).More than ‘The Peanut Man’. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2014/02/25/more-peanut-man